In ‘The Idealist’ my contribution to the recent Betrayal anthology, Statia Mitela could not have fulfilled her mission in 1849 Rome without these roads built by her ancestors and which have endured as routes and often the only properly paved road in the area through the millennia.

You can find Roman roads (viae Romanae), whether almost fully intact or reduced to little more than a trackway, all over Europe, even in the barbarous little island to the north called Britannia. The one in the photo is the Via Domitia at Ambrussum, near Nimes in southern France which provided a fast and sure link from Spain to Italy and northwards up the Rhone valley. It was built in 118 BC by the proconsul Gnaeus Domitius Ahenobarbus and is still with us, wheel ruts and all, over 2,000 years later.

If you asked people what defined Roman engineering, Roman roads would lie towards the top of the list. They were the physical infrastructure vital to the maintenance and development of the Roman state and were built from about 300 BC through the expansion and consolidation of the Roman Republic and the Roman Empire.

Primarily, the roads were for military use as a quick and efficient means for overland movement of armies and officials However, they also allowed the movement of people and goods, and connected isolated communities, helping them to absorb new ideas and influences, sell surplus goods, and buy what they could not produce locally. This trade resulted in an increase of wealth for everyone to a level not seen before and is suggested as a strong reason why many people strove to adopt the lifestyle of their conquerors.

These Roman roads ranged from small local roads to broad, long-distance highways built to connect cities, major towns and military bases. These major roads were often stone-paved and metalled, cambered for drainage, and flanked by footpaths, bridleways and drainage ditches. They were laid along accurately surveyed courses and some cut through hills or over rivers and ravines on complex bridgework. Sections could be supported over marshy ground on rafted or piled foundations.

Roman surveyor with groma (left) and dioptra (right) at the Eboracum Roman Festival 2019 (Author photo)

The Roman surveyors (agrimensores) were highly skilled professionals, able to use a number of tools, instruments, and techniques to plan the courses for roads and aqueducts, and lay the groundwork for towns, forts and large buildings. We half-jokingly talk about the Romans and their straight roads, but that throwaway statement is not far away from the truth. Much more about surveyors, techniques and instruments at https://explorable.com/roman-roads.

Some numbers

At the peak of Rome’s development, no fewer than 29 great military highways radiated from the capital, and the late Empire’s 113 provinces were interconnected by 372 great roads. The whole comprised more than 400,000 kilometres (250,000 miles) of roads, of which over 80,500 km (50,000 mi) were stone-paved. In Gaul alone, no less than 21,000 km (13,000 mi) of roadways are said to have been improved, and in Britain at least 4,000 km (2,500 mi). The courses (and sometimes the surfaces) of many Roman roads survived for millennia; quite a number have been overlaid by modern roads.

So were all roads like the ones in the movies?

No. Like ours today, they had different uses and were built to different specifications.

Viae publicae, consulares, praetoriae and militares

The first type of road included public main roads, constructed and maintained at the public expense; the state owned the land they were built on. Such roads led either to the sea, or to a town or to another public road.

Roman roads were often named after the censor who ordered their construction or reconstruction. That same person often served afterwards as consul, but the road name is dated to his term as censor. If the road was older than the office of censor or was of unknown origin, it took the name of its destination or of the region through which it mainly passed. A road was renamed if the censor ordered major work on it, such as paving, repaving, or rerouting.

Viae privatae, rusticae, glareae and agraria

The second category included private or country roads, originally constructed by private individuals, who owned the land they were built on and who had the power to dedicate them to the public use. Such roads benefited from a right of way, in favour either of the public or of the owner of a particular estate. Viae privatae were also included roads leading from the public or high roads to particular estates or settlements.

Roads off the main via were connected by viae rusticae, or secondary roads. Both main or secondary roads might either be paved, or left unpaved, with a gravel surface, as they were in North Africa. These prepared but unpaved roads were viae glareae or sternendae (“to be strewn”). Beyond the secondary roads were the viae terrenae, “dirt roads”.

Viae vicinales

The third category comprised roads at or in villages, districts, or crossroads, leading through or towards a vicus or village. Such roads ran either into a main road or into other viae vicinales without any direct communication with a high road. They were considered public or private, according to whether they were funded by public or private funds or materials. Even if privately constructed, this type of road became a public road when the memory of its private constructors had perished.

The repairing authorities in this case were the magistri pagorum or magistrates of the cantons. They could ‘require’ the neighbouring landowners either to provide labourers for the general repair of the viae vicinales or to keep in repair, at their own expense, a certain length of road passing through their respective properties. It was probably in their own interest anyway as without a good road farm produce couldn’t get to market.

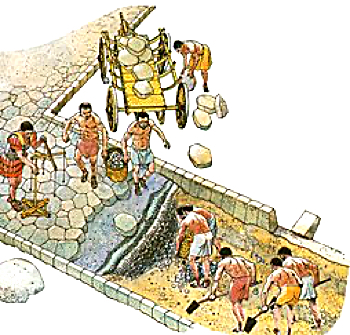

Building the roads

We have the funding and the responsibility, but who actually did the heavy lifting in the first place?

Building the main viae was a military responsibility and thus came under the jurisdiction of a consul. The process had a military name, viam munire, as though the via were a fortification. Municipalities, however, were responsible for their own local roads (viae vicinales).

The beauty and grandeur of the big roads might tempt us to believe that any Roman citizen could use them for free, but charging for using roads is not a new idea. Tolls abounded, especially at bridges. Often they were also collected at the city gate. Freight costs were made heavier still by import and export taxes, often between provinces. On Apulius’s journey to Virunum in The Girl from the Market, a customs official tries to extract duties as Apulius crosses from Raetia into Noricum on his way to his posting in Virunum.You can imagine the answer Apulius, as a serving military tribune, gave him…

These were only the charges for using the roads. Costs of services for the journey, e.g. horse, mule and carriage hire or haulage charges for goods was on top.

Along comes Augustus who tended to change everything…

In his overhaul of the urban administration, Augustus both abolished and created new offices for the maintenance of public works, streets and aqueducts in and around Rome. And, of course, he had Agrippa to supervise them with an unrivalled, almost frightening, efficiency. Emperors succeeding Augustus exercised vigilant control over the condition of public highways and their names occur frequently in the inscriptions to restorers of roads and bridges.

Down to the nitty-gritty

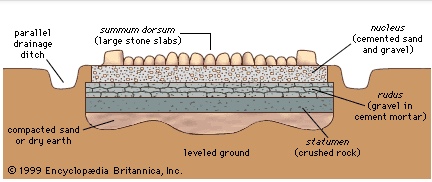

Roman road builders aimed at a regulation width, but actual widths have been measured at between 1.1 m (3.6ft) and more than 7 m (23ft) Today, the concrete has worn from the spaces around the stones, giving the impression of a very bumpy road, but the original practice was to produce a surface that was no doubt much closer to being flat. Many roads were built to resist rain, freezing and flooding and to need as little repair as possible. (Lessons for us today?)

Roman construction took a directional straightness(!). Many long sections are ruler-straight, but not all of them were. Some links in the network were as long as 89 km (55 mi). Gradients of 10%–12% are known in ordinary terrain, 15%–20% in mountainous country. The Roman emphasis on constructing straight roads often resulted in steep slopes relatively impractical for most commercial traffic; over the years the Romans themselves realised this and built longer, but more manageable, alternatives to existing roads. Roman roads generally went straight up and down hills, rather than in a serpentine pattern of switchbacks.

Materials and methods

Viae were distinguished not only according to their public or private character, but according to the materials employed and the methods followed in their construction.

- Via terrena: A plain road of levelled earth.

- Via glareata: An earthed road with a gravelled surface or or a gravel subsurface and paving on top.

- Via munita: A standard built road, paved with rectangular blocks of the stone of the country, or with polygonal blocks of lava.

The Romans, though certainly inheriting some of the art of road construction from the Etruscans, were said to have borrowed the knowledge of construction of viae munitae from the Carthaginians.

How far from A to B?

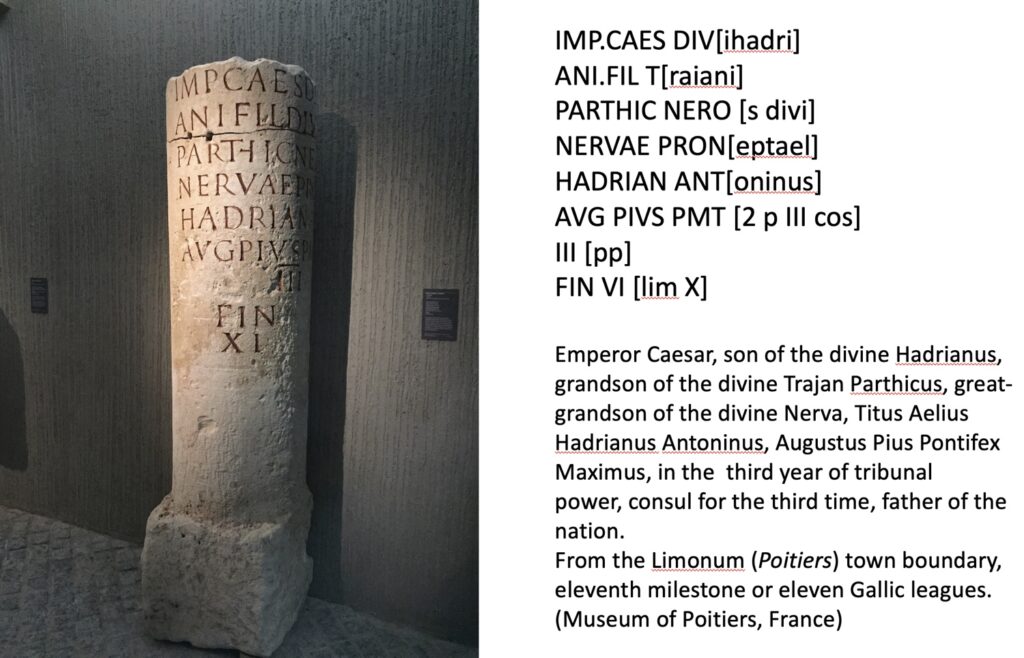

Milestones divided the via Appia even before 250 BC into numbered miles, and most viae after 124 BC. A milestone, or miliarium, was a circular column on a solid rectangular base, set for more than 2 ft/0.61m into the ground, standing 5ft/1.5m tall, 20in/51cm in diameter, and weighing more than 2 tons. At the base was inscribed the number of the mile relative to the road it was on.The milestone below dates from the time of Antoninus Pius (138-161 AD).

When Augustus, after becoming permanent commissioner of roads in 20 BC, set up the miliarium aureum (“golden milestone”) near the Temple of Saturn a panel at eye-height on milestones showed the distance to the Roman Forum as well as various other details about the officials who made or repaired the road. All roads were considered to begin from this gilded bronze monument. On it were listed all the major cities in the empire and distances to them.

And as we know, all roads lead to Rome.

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email newsletter. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Thank you so much for this fascinating article. I have always been in awe of Roman engineering, especially their roads and aqueducts. Of course that’s not not lessen their building achievements.

I thoroughly enjoyed researchng this. I have walked a lot of ‘Roman miles’ and it was a pleasure to share some of it.

[…] If you want to know more about how and where Roman roads were built, you might find this post interesting: On the Road to Rome. […]