Of all the ‘what ifs’ of history, the death of Emperor Julian in AD 363 has to be one of the most intriguing. He rejected Christianity, demoted its by then prominent place in the Roman state and promoted Neoplatonic Hellenism in its place. His aim was to reduce Christianity to one of many also-ran eastern cults and restore the traditional Roman gods as the state religion.

Of all the ‘what ifs’ of history, the death of Emperor Julian in AD 363 has to be one of the most intriguing. He rejected Christianity, demoted its by then prominent place in the Roman state and promoted Neoplatonic Hellenism in its place. His aim was to reduce Christianity to one of many also-ran eastern cults and restore the traditional Roman gods as the state religion.

If he had lived, could he have succeeded? Scholars have scratched their brains out arguing all sides of the counterfactual possibility. We fiction writers can be a little more imaginative…

Julian was the last ‘pagan’ emperor of the Roman Empire and reigned from AD 331 to 26 June 363. He’d been the Caesar of the West (a deputy to the augustus, Emperor Constantius II) from 355 to 360 and was a notable philosopher and author in Greek. The Christians called him Julian the Apostate as he’d been brought up as a Christian before he’d renounced it. Admirers call him Julian the Philosopher.

Who was Julian?

Flavius Claudius Julianus was born in AD 331, a nephew of Constantine the Great and one of the few in the imperial family to survive the purges and civil wars after Constantine’s death. Julian became an orphan at six years old after his father was executed in 337 and spent much of his life under the supervision of Constantius II, Julian’s cousin and the winner of the Roman game of thrones purge. However, Constantius allowed Julian to pursue an education in the Greek-speaking east, with the result that Julian became unusually cultured for an emperor of his time.

In 355, Constantius II summoned Julian to court and appointed him to rule Gaul. The young man was supposed to be only a figurehead, a nominal representative of imperial power. But despite his inexperience, Julian showed unexpected success as an administrator and in defeating and counterattacking Germanic raids across the Rhine.

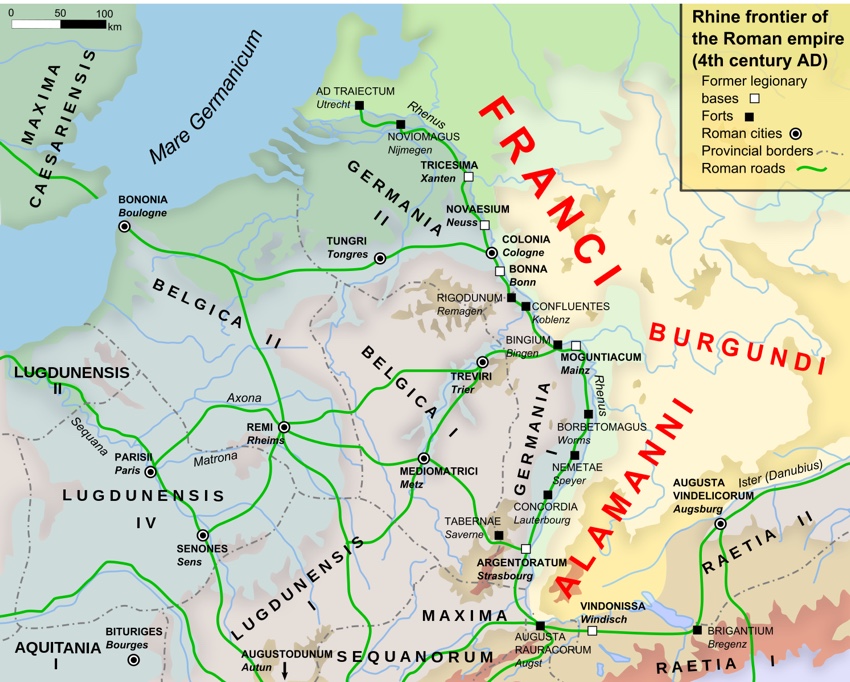

Most outstanding was the Battle of Argentoratum (Strasbourg), fought in AD 357 against the Alamanni tribal confederation led by the joint paramount King Chnodomar. Although a hard-fought battle, the Roman army won a decisive victory and drove the Alamanni beyond the River Rhine, inflicting heavy losses with few casualties on its own side. (In JULIA PRIMA, her father, Prince Bacausus, refers to fighting in that battle at Julian’s side.)

Original: ArdadN at English Wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

The battle was the highlight of Julian’s campaigns in 355–57 to evict barbarian marauders from Gaul. The troops respected him immensely as a result. In the years following his victory at Strasbourg, Julian was able to repair and garrison the Rhine forts, which had been largely destroyed during the Roman civil war of 350–53 and impose tributary status on the Germanic tribes beyond the border. So no slouch in emperor skills!

But there were consequences…

In the fourth year of Julian’s time in Gaul, the Sassanid emperor, Shapur II, invaded Mesopotamia and took the city of Amida. If it wasn’t the Parthians, it was the Sassinids who were the eastern thorn in the Roman Empire’s side. Constantius immediately swung his attention to marching east to deal with it. In February 360, he ordered more than half of Julian’s Gallic troops to join his eastern army. But his order didn’t go via Julian; Constantius by-passed him and went directly to Julian’s military commanders. A bit of a snub, to say the least.

At first, Julian tried to implement the order. However, it provoked an insurrection by troops who had no desire to leave Gaul. According to the historian Zosimus, the army officers leading the rebellion were responsible for distributing an anonymous tract expressing complaints against Constantius as well as fearing for Julian’s ultimate fate.

In 360, Julian’s soldiers proclaimed him augustus, i.e. full emperor, at Lutetia (Paris). This is always dangerous when there is already a ruling emperor. Constantius was beyond furious, but because of the immediate Sassanid threat, he was unable to directly respond to his cousin’s usurpation. He sent letters of varying level of threats and persuasion in which he tried to convince Julian to resign the title of augustus and be satisfied with that of caesar.

But Julian went back to business as usual in Gaul and from June to August of that year, he led a successful campaign against the Attuarian Franks. In November, Julian began openly using the title augustus, even issuing coins with the title, sometimes with Constantius, sometimes without.

Things were bound to come to a head sooner or later…

In the spring of AD 361, Julian pro-actively led his army into the territory of the Alamanni, where he captured their king, Vadomarius. Julian claimed that Vadomarius had been in league with Constantius, encouraging him to raid the borders of Raetia – Julian’s territory. Julian then divided his forces, sending one column to Raetia, one to northern Italy and the third he led down the Danube on boats. He was now well out of his comfort zone and on the road to civil war. Julian would state in late November that he set off down this road “because, having been declared a public enemy, I meant to frighten him [Constantius] merely, and that our quarrel should result in intercourse on more friendly terms…”

By AD 361, Constantius saw no alternative but to face the Julian with force, and yet the threat of the Sassanids remained. Constantius had already spent part of the early part of the year attempting – unsuccessfully – to re-take the fortress of Ad Tigris. He withdrew to Antioch to regroup but the campaigns of the previous year had inflicted heavy losses on the Sassanids and they did not attempt another campaign that year. This temporary respite in hostilities allowed Constantius to turn his full attention to confronting Julian.

However, Constantius died before the two could face each other in battle. Curiously, and perhaps on his deathbed remembering that the empire had to be passed on to an heir, he is supposed to have named Julian as his successor.

Julian as a different kind of emperor

The new emperor rejected the style of administration of his immediate predecessors. He viewed the royal court of his predecessors as inefficient, corrupt and expensive. Thousands of servants, eunuchs and superfluous officials were summarily dismissed. Julian’s own philosophic beliefs led him to idealise the reigns of Hadrian and Marcus Aurelius. He described the ideal ruler as being essentially primus inter pares (first among equals), operating under the same laws as his subjects. While in Constantinople, it wasn’t strange to see Julian frequently active in the Senate, participating in debates and making speeches, as if her were just another member of the Senate.

Amongst administrative measures, he cancelled arrears of land taxes.This was a key reform reducing the power of corrupt imperial officials, as the unpaid taxes on land were often hard to calculate or higher than the value of the land itself. Forgiving back taxes both made Julian more popular and allowed him to increase collections of current taxes. (We all love a tax break.)

Turning eastwards

In 363, Julian embarked on an ambitious campaign against the Sasanian Empire. It was partly to deal with the threat that Constantius had faced in 361 – unfinished business for Rome – and partly to achieve a victory that would reconcile the eastern army to him. The campaign was initially successful, securing a victory outside Ctesiphon in Mesopotamia. Instead of besieging the strongly defended capital, Julian moved into Persia’s heartland. Unfortunately, he soon faced supply problems and was forced to retreat northwards while being constantly harassed by Persian skirmishers.

During the Battle of Samarra, in the haste of pursuing the retreating enemy, Julian chose speed over caution, taking only his sword and leaving his coat of mail. A spear caught him in the side, reportedly piercing the lower lobe of his liver and intestines. On the third day, he suffered a major haemorrhage and died during the night. As Julian wished, his body was buried outside Tarsus, though it was later moved to Constantinople.

4th-century cameo of an emperor, probably Julian, performing sacrifice, National Archaeological Museum, Florence (, CC BY 3.00

The last non-Christian Roman emperor

Julian had believed that he needed to restore the Empire’s ancient Roman values and traditions in order to save it from dissolution. He purged the top-heavy state bureaucracy, and attempted to revive traditional Roman religious practices at the expense of Christianity. He restored pagan temples which had been confiscated since Constantine’s time, or simply appropriated by wealthy citizens; he repealed the stipends that Constantine had awarded to Christian bishops, and removed their other privileges, including a right to be consulted on appointments and to act as private courts. Julian also forbade Christians from teaching and learning classical texts.

His wish was to create a society in which every aspect of the life of the citizens was to be connected, through layers of intermediate levels, to the consolidated figure of the emperor – the final provider for all the needs of his people. Within this project, there was no place for a parallel institution, such as the Church’s hierarchy or Christian charity.

He was a motivated writer of many letters, panegyrics, philosophical works and poems, few of which have survived. But his life and philosophy have made him an intriguing subject throughout the centuries.

But what if Julian had lived to reign another ten, twenty or even thirty years? Would he have rolled back Christianity’s dominant hold on the Roman state and changed history?

The ‘No’ case

Christianity was still a minority religion in the 360s but it was well organised with regional bases, bishops, vigorous advocates and congregations. By the time Julian became emperor it had a firm hold on Roman society, especially on those who sought power and preferment from a Christian head of state.

The ‘Yes’ case

Julian was already having success in persuading, bribing, and threatening Christians to return to the ways of their ancestors while building up the ancient pagan temples and priesthoods. A proportion had become Christian in order to advance, for avoiding family discord, from peer pressure – all practical reasons. It was likely they would revert to the traditional gods for similar reasons. Along with (still) the majority of Romans, much of the aristocracy in Rome itself who still had considerable influence continued to hold to the traditional Roman gods in spite of increasing restrictions and defunding by the state treasury of its temples and priests.

The ‘Perhaps’ case

A more nuanced view is that Julian could never have eliminated Christianity, but if he managed to relegate it to just another minor sect among many in the religions in multi-faith Roman Empire, would it have mattered?

Julian could have reduced Christianity greatly if he’d lived longer and so had more time. In the hierarchical Roman Empire, the emperor was still the emperor and the one who possessed absolute power. He was completely focused on his goals, had a brilliant, well-educated mind and enjoyed the reputation of a successful military general. He also gave tax breaks and was an able administrator.

After Julian’s death, the Christian church strengthened its grip on every aspect of the Roman state in order that such a roll-back could never happen again. Once bitten, twice shy.

Of course, the subsequent course of European, possibly world history would have been very different if Julian had achieved his aims – no Inquisition, Crusades or Reformation. Perhaps the big clash of history would have been Romans vs. the Arabs.

As Tertullius Plico said to Aurelia Mitela in Roma Nova in the late 1960s, “The gods only know, and they’re not answering their phone.” [INSURRECTIO]

______________

Suggested further reading;

Julian, a novel by Gore Vidal (1964)

Christendom: The Triumph of a Religion, AD 300-1300 – Peter Heather

The Darkening Age: The Christian Destruction of the Classical World – Catherine Nixey

Alison Morton is the author of Roma Nova thrillers – INCEPTIO, CARINA (novella), PERFIDITAS, SUCCESSIO, AURELIA, NEXUS (novella), INSURRECTIO and RETALIO, and ROMA NOVA EXTRA, a collection of short stories. Audiobooks are available for four of the series. Double Identity, a contemporary conspiracy, starts a new series of thrillers. JULIA PRIMA, Roma Nova story set in the late 4th century, starts the Foundation stories. The sequel, EXSILIUM, is now out.

Download ‘Welcome to Alison Morton’s Thriller Worlds’, a FREE eBook, as a thank you gift when you sign up to Alison’s monthly email update. You’ll also be among the first to know about news and book progress before everybody else, and take part in giveaways.

Leave a Reply